Electric vehicles (EVs) represent a cornerstone of clean urban mobility, yet access to charging remains a persistent barrier for millions of city residents. For renters and apartment dwellers, the lack of private garages or dedicated parking often translates into a complete absence of home charging options.

This inequity disproportionately affects lower-income households and communities of color, groups already burdened by transportation-related air pollution.

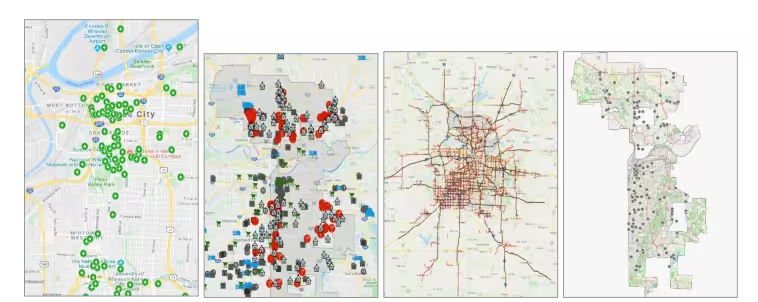

Researchers at Penn State University, in collaboration with the Metropolitan Energy Center (MEC) and Kansas City, Missouri, launched a pioneering initiative to address this challenge. The pilot retrofitted 23 city streetlights into EV charging stations and evaluated performance across all six council districts, as documented in the project’s final report.

The Accessibility Gap: Why Renters and Low‑Income Drivers Struggle

Charging Deserts in Urban America

About 80% of charging happens at home, which leaves renters without dedicated parking at a disadvantage, yet more than one‑third of U.S. households, and over half in major metro areas, live in multifamily housing where private charging is impossible. Apartment dwellers face legal and logistical hurdles to installing chargers, leaving them dependent on sparse public networks.

Without curbside access, even affordable EVs remain out of reach. MEC’s report highlights that multifamily residents lack practical charging access, limiting their participation in the clean‑energy transition.

The Human Cost of Inaccessibility

In focus groups, renters described EV ownership without home charging as a “daily headache.” They frequently drove out of their way to find public stations, a costly and time‑consuming burden. These “charging deserts” often align with low‑income neighborhoods, compounding existing environmental and economic inequalities.

Equity‑Focused Framework: Merging Demand and Social Data

Penn State, NREL, and MEC implemented a two-tiered site-selection framework that combines a demand model with an equity screen:

Tier 1: Demand Modeling: The first layer used a boosting-based ensemble model trained on six years of regional charging data, incorporating land use, traffic, trip generation, and points of interest (POIs).

Tier 2: Equity Analysis: The second layer, led by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), overlaid demographic and socio-economic indicators using EPA’s EJSCREEN. Neighborhoods were grouped into three strategic categories.

| Category | Description | Strategic Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Easy Win | High EV ownership but poor charging access | Meet immediate demand and ensure utilization |

| Unlock Potential | Low EV use but favorable demographics | Stimulate emerging adoption markets |

| Create Opportunity | Low‑income areas with high multifamily share | Build new access points and promote equity |

By combining demand and equity layers, the framework ensured chargers were placed not only where they’d be used most, but where they were needed most.

Community Engagement: Ground‑Truthing Through Local Voices

Early feedback showed modeling alone was insufficient, so the team shifted to community-driven planning with listening sessions and paid outreach, revising sites accordingly.

Shifting from Consultation to Collaboration

MEC and its partners pivoted toward community‑driven planning. They organized listening sessions, distributed bilingual outreach materials, and compensated participants for their time. Local advocacy groups such as EVNoire and Westside Housing Organization facilitated dialogue in historically underserved districts.

Community‑Driven Priorities

Residents prioritized chargers near grocery stores, schools, and parks, safe, familiar spaces with daily foot traffic. They also raised safety and accessibility concerns, noting that many potential sites lacked adequate sidewalks or lighting. In response, planners revised site maps to balance feasibility with fairness, ensuring every Kansas City council district received installations.

This engagement transformed the pilot into a co‑created public service, proving that community input is as vital as data modeling for equitable infrastructure deployment.

Usage Patterns: What the Data Revealed

Once operational, the 23 streetlight chargers provided a rich dataset for evaluation. Evergy monitored performance using quarterly ChargePoint reports, and the analysis in the final report covers Q3–Q4 FY 2023.

- Utilization Across Income Levels: All chargers recorded usage. On average, each unit logged 74 charging sessions, with no major disparity between high- and low-income areas, and MEC reports no major disparity in use across income levels in Q3 FY 2023.

- Influence of Points of Interest (POIs): Stations near multiple POIs saw the highest demand, for example, 575.36 hours at a site near parks, dog parks, and pools, versus 0.87 hours at a site near only an apartment complex and a cemetery. These paired examples illustrate how colocating with everyday destinations correlates with markedly higher charging time.

- Environmental Impact: During the analysis period, the stations delivered 30,465 kWh, with 3,823 gallons of gasoline offset and 21,711 kg CO₂e avoided. Each CT4000-series Level 2 charger adds roughly 25 miles of range per hour, depending on vehicle and power settings, making it ideal for overnight or multi‑hour parking.

- Cost Efficiency: Installation costs ranged from approximately $13,000 to $45,000 per site, depending on required electrical upgrades, still below conventional curbside chargers requiring trenching or conduit work. In the U.K., on-street lamppost chargers are installed directly into existing columns in just under two hours.

| Metric | Streetlight Chargers (Kansas City) | Conventional Curbside Chargers |

|---|---|---|

| Installation Cost | $13 k – $45 k | $13 – $45 k |

| Deployment Time | 1–2 weeks | 1–2 months |

| GHG Reduction | 21.7 metric tons CO₂e | N/A (varies by location) |

Broader Implications: Bridging Charging Deserts Nationwide

The Kansas City pilot validated that repurposed streetlights can democratize access to EV charging without major urban disruption. Aligns with the Justice40 Initiative goal that 40% of overall benefits flow to disadvantaged communities; clean transportation is one of the covered program areas.

Kansas City distributed 23 chargers across all six council districts and combined demand modeling with an equity screen and community input to site locations. By combining cost‑effective engineering, community partnership, and data‑driven planning, the Penn State framework offers a scalable path for cities nationwide.

As EV adoption accelerates, this approach can convert thousands of existing streetlights into accessible curbside chargers, transforming “pavement without power” into an inclusive engine for clean mobility.

Conclusion: Lighting Streets, Powering Futures

The Kansas City streetlight EV charging pilot proves that equitable electrification is not only possible but practical. By adapting existing infrastructure, engaging residents, and grounding site selection in both data and local knowledge, the project achieved what traditional top‑down planning rarely does: real access for real people.

As cities across the U.S. confront rising EV demand, the lesson is clear: the road to sustainable mobility can begin with the lights already shining above our streets.